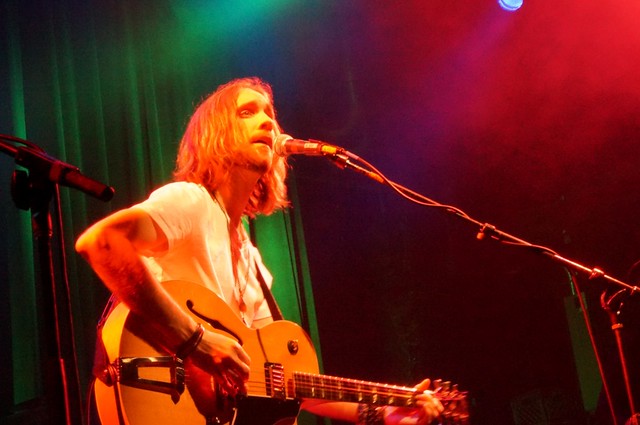

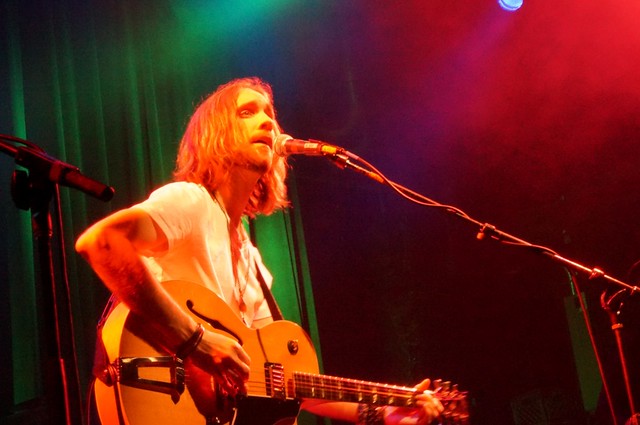

In part one of my interview with singer/songwriter Pete Pidgeon of Arcoda, we talked about his musical approach, his insights into the Front Range music scene, and how his career has developed, both here and on the East Coast. Part two finds us discussing his influences, some of the recognition he's received and exactly what to do (and what not to do) if you find yourself face to face with Paris Hilton or Trey Anastasio.

Enjoy part two of our conversation, which has been condensed and lightly edited.

Earlier, you mentioned that the legendary Levon Helm of The Band contributed to your upcoming album. How was it playing with him?

Pete Pidgeon: It’s still number one. It’ll probably always be number one. One of my earliest memories, my parents were big music fans. They had a huge vinyl collection, which really influenced where I came from. Randy Newman, Bonnie Raitt, Paul Simon, Billy Joel...all these great singer-songwriters. They had Big Pink and they put on “Chest Fever” and I remember this distinctly. I would crawl up on the couch and jump on the couch when they’d play music. So I remember doing that and then “Chest Fever” coming on and being completely terrified, because it was the scariest sounding organ. It was this huge, monstrous Garth Hudson organ sound. It was overwhelming how powerful this tune was. From my earliest memories of music, I’ve been exposed to The Band and Levon’s playing.

The biggest thing about Levon is that, of anybody in the last 50 years or so who cared more about music, I think he’s probably the number one dude. I don’t think anybody cared more about playing as hard as he could every single night and really giving everything he had to the music. There was this story that Larry Campbell said, if I’m not wrong. [ed: Theresa Williams mentions it in this interview on For the Country Record] In his last days, when he was playing a show, he was sitting in the corner of the room and he wasn’t even talking to anybody. He was talking to himself and talking to God, and saying, “All I ask for is just these 90 minutes on stage. That’s all I ask for. The other hours of the day? Whatever. You want to make me sick, that’s fine, but I need these 90 minutes right here to go out.” You can’t get bigger than that. So, the honor of being able to make music with him, to have him play my music? Come on. That’s just the biggest honor of all time.

Your bio includes things like the Jeff Buckley tribute, which I think exposed you to a lot of bigger named people and gave you some public visibility. I’ve also seen that you were in the running for some Grammys in 2012.

PP: Yeah, ‘11-’12. The ceremony was in 2012, but it was for the 2011 Grammys.

What categories were you considered for?

PP: It was for the EP called Growing Pains. There was a single on there called “Will” and we did a music video for it.

Oh yeah, I saw that on YouTube. Didn’t you write the storyline?

PP: I directed it. I co-wrote the story with Wes Mock, but I wrote the screenplay for it. And I did all the fieldwork for it and financed it.

That was a pretty heavy video.

PP: Thanks. It was dealing with some serious issues. I was volunteering at the time at Road Recovery, which helps children dealing with addictions. A lot of those kids were going through suicide problems and really major stuff. It was actually written about this girl, I’m sure she was suicidal, but I can’t tell you that for sure. But going through a major breakup: outside the lines of regular people breakup. Major stuff. She just had a huge impact on me and I wrote a few tunes about her and that was one of them. “I am more than the sum of my mistakes;” that’s the lyric that everyone responds to. She made these mistakes, but they weren’t really her fault, necessarily. It just had a big impact.

So, that video got nominated for Best Short Form Video, the single, “Will” was nominated for Song of the Year and Record of the Year. And then I was also up for Best Rock Performance and Best Rock Song.

But I’m very clear to mention that these were Grammy-recognized. That’s because a technical Grammy nomination only refers to the top five people that go to the awards ceremony. We made the second round of three, with the third round being the Top Five nominations.

I also noticed that you’re teaching guitar here, which is a good way to make ends meet as a musician. What’s your teaching philosophy?

PP: My curriculum is based on the individual student. Some kids want to learn theory, some kids don’t want to learn theory. Some kids want to learn how to play heavy metal, some kids want to play folk songs or pop tunes. When I came up, I didn’t have a teacher. My brother and my father taught me how to play guitar, but they weren’t sitting there saying, “This is how you’re supposed to do it. You need to learn these songs and do this.” It was more like coaching. So, with my students, I try to incorporate that into the lesson.

I’m glad you brought up your roots. I was wondering what your family background was with music. You mentioned your parents’ vinyl collection and now that your dad and brother both play.

PP: Yeah, my dad and my brother both play guitar. My dad was a campfire folk singer: Everly Brothers, Beach Boys, that kind of thing. Even way back in the day, when he was in high school and college, he had a couple of bands and was doing that style of music. My mom played piano and sang. My dad sang and played guitar. And my grandmother, my mother’s mother, she loved playing piano, too., She played at Christmas and I think she played at church at one point. Her husband, my mom’s father, was in the church. He played hymns and stuff on the piano. He died before I was born, but my grandma played a lot of those tunes. So there was a lot of music in the house. We had a music room in the house...My family called it the living room, but I called it the music room because it had baby grand piano, a bunch of guitars, xylophones, percussion instrument, trombone, violins, trumpet, recorders, flute. There was just all sorts of instruments, plus the record player, the reel-to-reel player. I couldn’t ask for more, you know.

Do you just have the one brother? Does he play as a hobbyist?

PP: Yes. The first live gig I ever played in public, I played bass in his progressive rock cover band. It was Yes, Rush, Triumph and maybe a couple of other groups, but that was the core of it. I was either 13 or 14. They were playing “Yours is No Disgrace” [by Yes] and the bass player couldn’t hang with the bass part. It wasn’t necessarily technically difficult, but there’s a lot of notes to memorize, and there’s a bass solo and stuff. A walking bass thing. So I just picked it up and played it. So, my brother brought me on because I could play the whole thing. They called me the Iceman, because I just stood in one place, staring at the bass, not moving, not looking at anybody.

Total shoegazer...

PP: Exactly. A shoegazer before shoegazing. So he was a shredder into progressive rock and shred: Satriani, Malmsteen, and Vai, Paul Gilbert, that kind of thing. He was a major influence. Probably the biggest influence. He had a bunch of bands. He doesn’t gig out as much now, but he definitely gave it a good go for a long time.

What other influences would you cite for your music?

PP: Oh, Man. it’s been a long road. The first exposure was the singer-songwriters that I mentioned. The first band I liked on my own was Huey Lewis and the News. There was this one live performance of "The Power of Love", where he’s playing onstage and he gets on his knees and he’s just yelling. I was like, “That’s amazing. That the coolest.” I must’ve been around 7 or 8.

I saw Robert Palmer when “Addicted to Love” came out and he had that video with all the girls dressed in black and doing their thing. I didn’t know what love was at the time or what any of the lyrics were about, which my parents found amusing, but I saw that video and I connected with it right away. I thought, “This is the greatest music I’ve ever heard.”

And there was a black and white Kiss show that I remember from when I was super young. Just the fact that I remember these things means that my brain was hardwired for music. I’m barely an infant and I recognize what’s going on.

So that was the earliest stuff. Then my brother got me into progressive rock and shred and then that graduated into jazz in high school and college. Then that graduated into jam bands: Allman Brothers, Phish, Dead, Santana, that kind of stuff, which taught me how to improvise. Coming out of progressive rock and shred, there’s no improvisation. Although there was some in Yes, I’ll give them some credit because they were an organic progressive band.

So I did the jam band thing. After that, I started getting back into my roots of songwriting, around ‘03. I’ve sort of been in that scene for the last ten years: song craft, how to write better tunes. Definitely more stripped down, trying to make it more compact. That’s one thing New York definitely taught me: you got to have a three minute tune. maybe a four minute tune if you can, but no more of this 7 or 8 minute progressive, long form stuff, That was sort of the purpose of the Growing Pains EP. How can I be concise and write a hit tune or a radio tune? And it’s still too progressive for most people, but it’s the best I could do without sacrificing my creative interests.

You brought up the jam band thing, which is a good segue, because I wanted to talk briefly with you about your book, Hampton '98: The Dephinitive Experience about the Hampton shows and Phish. I read the interview you had with Glide and I found it really intriguing. I wanted to ask you was about a teaser quote from that Glide interview. You talked about getting experience meeting the guys in Phish and that you finally learned how to meet and talk to famous people. So what’s your advice for people? What is the proper way?

PP: (laughs) It’s exactly how you and I are talking right now. That’s exactly how you do it. You’re just another dude. “Hey what’s going on? What do you have happening? How’s the road been? What’s up?” and not get overtaken. It’s easier said than done, but not get overtaken by -- there’s almost a palpable energy that comes off of people that are famous. I don’t know why. I’m theorizing that it has something to do with their influence and also how they’ve been influenced. The amount of energy that they can play in front of 100,000 people and affect 100,000 people simultaneously by playing one note on their instrument or them being influenced by those 100,000 people giving all their energy back to them. They’re very electric people.

If you can talk to your brain and say, “Just be cool, man, it’s just a normal person,” have a regular convo, keep it on the level. I think that breathing and pausing is a big part of it. Because your brain’s on fire, “Oh my God, I’m talking to this person, this is so amazing! Keep talking, keep talking!” But if you can have that natural flow of conversation, you have to consciously put that pause in between your sentences, so you’re not just blasting this poor person the whole time. That’s what makes them anxious and not want to really hang out and talk. You’re just throwing so much at them, so fast.

One of the hardest parts is that there’s so many things that you want to tell this person and you don’t have more than probably 15 seconds to get it out and you’re probably going to screw it up and you’re probably also going to forget all those things and just say something, The first time I met Trey [Anastasio] was like that. I met him outside of his lodge at Sugarbush in 1995. I was just, “blah, blah, blah”, you know. I couldn’t really form sentences and said stupid things. I gave him a hug and he was all freaked out. Good for him, because I freaked him out. Over the years, I’ve tried to tone it down.

But battling the energy field is still difficult. Like being at the Grammys on the red carpet with Paris Hilton and Sting where you are right now. Just being cool, “Hey what’s up Paris, How are you doing?” “Oh, I’m a little cold.” “Have you got a sweater?” “No, I didn’t bring one…” Just bullshitting, but that goes a long way. Just be a normal person, you know.

Thanks for being a normal person for this interview

PP: (laughs) Hopefully, I can be one for the rest of my life.

Enjoy part two of our conversation, which has been condensed and lightly edited.

Earlier, you mentioned that the legendary Levon Helm of The Band contributed to your upcoming album. How was it playing with him?

Pete Pidgeon: It’s still number one. It’ll probably always be number one. One of my earliest memories, my parents were big music fans. They had a huge vinyl collection, which really influenced where I came from. Randy Newman, Bonnie Raitt, Paul Simon, Billy Joel...all these great singer-songwriters. They had Big Pink and they put on “Chest Fever” and I remember this distinctly. I would crawl up on the couch and jump on the couch when they’d play music. So I remember doing that and then “Chest Fever” coming on and being completely terrified, because it was the scariest sounding organ. It was this huge, monstrous Garth Hudson organ sound. It was overwhelming how powerful this tune was. From my earliest memories of music, I’ve been exposed to The Band and Levon’s playing.

The biggest thing about Levon is that, of anybody in the last 50 years or so who cared more about music, I think he’s probably the number one dude. I don’t think anybody cared more about playing as hard as he could every single night and really giving everything he had to the music. There was this story that Larry Campbell said, if I’m not wrong. [ed: Theresa Williams mentions it in this interview on For the Country Record] In his last days, when he was playing a show, he was sitting in the corner of the room and he wasn’t even talking to anybody. He was talking to himself and talking to God, and saying, “All I ask for is just these 90 minutes on stage. That’s all I ask for. The other hours of the day? Whatever. You want to make me sick, that’s fine, but I need these 90 minutes right here to go out.” You can’t get bigger than that. So, the honor of being able to make music with him, to have him play my music? Come on. That’s just the biggest honor of all time.

Your bio includes things like the Jeff Buckley tribute, which I think exposed you to a lot of bigger named people and gave you some public visibility. I’ve also seen that you were in the running for some Grammys in 2012.

PP: Yeah, ‘11-’12. The ceremony was in 2012, but it was for the 2011 Grammys.

What categories were you considered for?

PP: It was for the EP called Growing Pains. There was a single on there called “Will” and we did a music video for it.

Oh yeah, I saw that on YouTube. Didn’t you write the storyline?

PP: I directed it. I co-wrote the story with Wes Mock, but I wrote the screenplay for it. And I did all the fieldwork for it and financed it.

That was a pretty heavy video.

PP: Thanks. It was dealing with some serious issues. I was volunteering at the time at Road Recovery, which helps children dealing with addictions. A lot of those kids were going through suicide problems and really major stuff. It was actually written about this girl, I’m sure she was suicidal, but I can’t tell you that for sure. But going through a major breakup: outside the lines of regular people breakup. Major stuff. She just had a huge impact on me and I wrote a few tunes about her and that was one of them. “I am more than the sum of my mistakes;” that’s the lyric that everyone responds to. She made these mistakes, but they weren’t really her fault, necessarily. It just had a big impact.

So, that video got nominated for Best Short Form Video, the single, “Will” was nominated for Song of the Year and Record of the Year. And then I was also up for Best Rock Performance and Best Rock Song.

But I’m very clear to mention that these were Grammy-recognized. That’s because a technical Grammy nomination only refers to the top five people that go to the awards ceremony. We made the second round of three, with the third round being the Top Five nominations.

I also noticed that you’re teaching guitar here, which is a good way to make ends meet as a musician. What’s your teaching philosophy?

PP: My curriculum is based on the individual student. Some kids want to learn theory, some kids don’t want to learn theory. Some kids want to learn how to play heavy metal, some kids want to play folk songs or pop tunes. When I came up, I didn’t have a teacher. My brother and my father taught me how to play guitar, but they weren’t sitting there saying, “This is how you’re supposed to do it. You need to learn these songs and do this.” It was more like coaching. So, with my students, I try to incorporate that into the lesson.

I’m glad you brought up your roots. I was wondering what your family background was with music. You mentioned your parents’ vinyl collection and now that your dad and brother both play.

PP: Yeah, my dad and my brother both play guitar. My dad was a campfire folk singer: Everly Brothers, Beach Boys, that kind of thing. Even way back in the day, when he was in high school and college, he had a couple of bands and was doing that style of music. My mom played piano and sang. My dad sang and played guitar. And my grandmother, my mother’s mother, she loved playing piano, too., She played at Christmas and I think she played at church at one point. Her husband, my mom’s father, was in the church. He played hymns and stuff on the piano. He died before I was born, but my grandma played a lot of those tunes. So there was a lot of music in the house. We had a music room in the house...My family called it the living room, but I called it the music room because it had baby grand piano, a bunch of guitars, xylophones, percussion instrument, trombone, violins, trumpet, recorders, flute. There was just all sorts of instruments, plus the record player, the reel-to-reel player. I couldn’t ask for more, you know.

Do you just have the one brother? Does he play as a hobbyist?

PP: Yes. The first live gig I ever played in public, I played bass in his progressive rock cover band. It was Yes, Rush, Triumph and maybe a couple of other groups, but that was the core of it. I was either 13 or 14. They were playing “Yours is No Disgrace” [by Yes] and the bass player couldn’t hang with the bass part. It wasn’t necessarily technically difficult, but there’s a lot of notes to memorize, and there’s a bass solo and stuff. A walking bass thing. So I just picked it up and played it. So, my brother brought me on because I could play the whole thing. They called me the Iceman, because I just stood in one place, staring at the bass, not moving, not looking at anybody.

Total shoegazer...

PP: Exactly. A shoegazer before shoegazing. So he was a shredder into progressive rock and shred: Satriani, Malmsteen, and Vai, Paul Gilbert, that kind of thing. He was a major influence. Probably the biggest influence. He had a bunch of bands. He doesn’t gig out as much now, but he definitely gave it a good go for a long time.

What other influences would you cite for your music?

PP: Oh, Man. it’s been a long road. The first exposure was the singer-songwriters that I mentioned. The first band I liked on my own was Huey Lewis and the News. There was this one live performance of "The Power of Love", where he’s playing onstage and he gets on his knees and he’s just yelling. I was like, “That’s amazing. That the coolest.” I must’ve been around 7 or 8.

I saw Robert Palmer when “Addicted to Love” came out and he had that video with all the girls dressed in black and doing their thing. I didn’t know what love was at the time or what any of the lyrics were about, which my parents found amusing, but I saw that video and I connected with it right away. I thought, “This is the greatest music I’ve ever heard.”

And there was a black and white Kiss show that I remember from when I was super young. Just the fact that I remember these things means that my brain was hardwired for music. I’m barely an infant and I recognize what’s going on.

So that was the earliest stuff. Then my brother got me into progressive rock and shred and then that graduated into jazz in high school and college. Then that graduated into jam bands: Allman Brothers, Phish, Dead, Santana, that kind of stuff, which taught me how to improvise. Coming out of progressive rock and shred, there’s no improvisation. Although there was some in Yes, I’ll give them some credit because they were an organic progressive band.

So I did the jam band thing. After that, I started getting back into my roots of songwriting, around ‘03. I’ve sort of been in that scene for the last ten years: song craft, how to write better tunes. Definitely more stripped down, trying to make it more compact. That’s one thing New York definitely taught me: you got to have a three minute tune. maybe a four minute tune if you can, but no more of this 7 or 8 minute progressive, long form stuff, That was sort of the purpose of the Growing Pains EP. How can I be concise and write a hit tune or a radio tune? And it’s still too progressive for most people, but it’s the best I could do without sacrificing my creative interests.

You brought up the jam band thing, which is a good segue, because I wanted to talk briefly with you about your book, Hampton '98: The Dephinitive Experience about the Hampton shows and Phish. I read the interview you had with Glide and I found it really intriguing. I wanted to ask you was about a teaser quote from that Glide interview. You talked about getting experience meeting the guys in Phish and that you finally learned how to meet and talk to famous people. So what’s your advice for people? What is the proper way?

PP: (laughs) It’s exactly how you and I are talking right now. That’s exactly how you do it. You’re just another dude. “Hey what’s going on? What do you have happening? How’s the road been? What’s up?” and not get overtaken. It’s easier said than done, but not get overtaken by -- there’s almost a palpable energy that comes off of people that are famous. I don’t know why. I’m theorizing that it has something to do with their influence and also how they’ve been influenced. The amount of energy that they can play in front of 100,000 people and affect 100,000 people simultaneously by playing one note on their instrument or them being influenced by those 100,000 people giving all their energy back to them. They’re very electric people.

If you can talk to your brain and say, “Just be cool, man, it’s just a normal person,” have a regular convo, keep it on the level. I think that breathing and pausing is a big part of it. Because your brain’s on fire, “Oh my God, I’m talking to this person, this is so amazing! Keep talking, keep talking!” But if you can have that natural flow of conversation, you have to consciously put that pause in between your sentences, so you’re not just blasting this poor person the whole time. That’s what makes them anxious and not want to really hang out and talk. You’re just throwing so much at them, so fast.

One of the hardest parts is that there’s so many things that you want to tell this person and you don’t have more than probably 15 seconds to get it out and you’re probably going to screw it up and you’re probably also going to forget all those things and just say something, The first time I met Trey [Anastasio] was like that. I met him outside of his lodge at Sugarbush in 1995. I was just, “blah, blah, blah”, you know. I couldn’t really form sentences and said stupid things. I gave him a hug and he was all freaked out. Good for him, because I freaked him out. Over the years, I’ve tried to tone it down.

But battling the energy field is still difficult. Like being at the Grammys on the red carpet with Paris Hilton and Sting where you are right now. Just being cool, “Hey what’s up Paris, How are you doing?” “Oh, I’m a little cold.” “Have you got a sweater?” “No, I didn’t bring one…” Just bullshitting, but that goes a long way. Just be a normal person, you know.

Thanks for being a normal person for this interview

PP: (laughs) Hopefully, I can be one for the rest of my life.

No comments:

Post a Comment