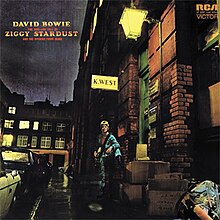

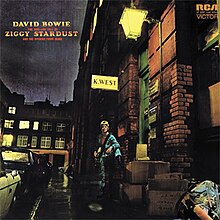

Bowie's transcendent concept album rippled into the real world

While David Bowie had achieved some commercial success with

Space Oddity,

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars transformed Bowie into a larger than life character. It's important to understand that

Ziggy was not just music; it was a full blown persona, a story, and a fashion palette. Along with Marc

Bolan (T. Rex), Bowie used this platform to define the androgynous look of glam rock. Ziggy also proved to be the first step in David Bowie's serial self-reinvention. Without Bowie-as-Ziggy, it's hard to imagine Madonna or Lady Gaga.

Ziggy was Bowie's first attempt at a concept album. The loose storyline sets up Ziggy as a Christ like figure, complete with a fall if not a resurrection. Compared to more fully realized works like the Who's

Tommy or Pink Floyd's

The Wall, Bowie's mirage-like structure doesn't stand up to focused attention largely because the story is barely sketched in. But Bowie's instinctive theatrical sense accented by the production makes

Ziggy connect on an emotional level. The lack of coherent detail in the narrative leaves room for interpretation, allowing an impression of completeness. As Bowie assumed Ziggy's persona off stage, he imbued the character with more depth, adding to the fascination.

Despite the flawed storyline, the musical flow has an unconscious perfection. The drum beat fade-in of

Five Years invites us into a story already in progress. The sparse arrangement is dominated by the drum beat and bass line. Bowie's lyrics paint an end-of-the-world scenario, but it's heavy with sentimentality. The maudlin sense thickens as the string backing fills in later. The arrangement subtly moves the song through a grieving process as the news sinks in. The treacly strings lose power to chaotic elements of denial and fear. Then the darkness fades, allowing a hint of acceptance before we fade out on the same drum beat of the beginning.

Soul Love paints a mixed picture of life after the news, with a narrator caught up in his own solitude. The horn solo foreshadows Bowie's later work on

Young Americans. The soft ending provides no warning for the opening punch of

Moonage Daydream. Ken Scott's psychedelic production shifts the tone of the album into its science fiction comfort zone. Mick

Ronson's guitar work subtly colors the track. His tone howls, but it's applied with restraint to get maximum effect. Then, in the final section,

Ronson slips free and lets it wail, surfing on some of the rage missing from

Five Years.

We get our first real taste of Ziggy and his message through

Starman. This is followed by the sole cover on the album, Ron Davies'

It Ain't Easy. Within the

Ziggy's context, the simple blues song becomes a key step in the story, indicating Ziggy's self discovery and hinting at his preordained fall: "

it ain't easy to get to heaven when you're going down."

On vinyl, the

Beatlesque coda of

It Ain't Easy meant it was time to turn the record. That pause was important. The ritualistic record flip gave you time to consider that

it wasn't easy, not to get to heaven or even get ahead. The break was a chance to appreciate that the first half of

Ziggy is the set up, an inhale to drive the quick power of the second half.

Lady Stardust gives us the first clear look at our androgynous hero in his initial perfection. The measured pace captures the magic of gazing on Ziggy, transfixed. This is followed by

Star. The

doo-wop tinged rocker reflects Ziggy's impact on his fans, pushing them to aspire to rock and roll themselves. Then the pace kicks up with

Hang On To Yourself. The beat is all over the place, with fast intervals between slower paced verses. The tempo speeds up to a breakneck pace for an orgiastic finish (

Come on, come on).

Next is the glam masterpiece of

Ziggy Stardust.

Ronson's guitar is perfect. The repetition of his opening line tells a story all by itself. Bowie begins the meat of Ziggy's story with the simplest of statements, "

Ziggy played guitar". The verses reminisce sweetly, but the picture isn't always pretty, contrasting Ziggy's charisma with his ego. The breaks are darker, sharing the jealousy of the Spiders and Ziggy's eventual end. It all wraps up where it started: "

Ziggy played guitar"

After this, we get the slightly out of place, but rocking

Suffragette City and the perfect ending of

Rock & Roll Suicide. This closer brings back the deliberate pace and darkness from

Five Years. But despite the heavy mood, it's the antithesis of

Soul Love. Where the former sadly notes that "

love is not loving",

Rock & Roll Suicide stages a full scale intervention: "

you're not alone/you're watching yourself but you're too unfair". It's theatrically grand and it ends with an echo of

It Ain't Easy's

Beatlesque finish.

It's a small loss when things we loved in our youth don't stand up to more experienced minds or our fond memories. An album that seemed like perfection at 14 may still be beloved at 40 while it's slipped from our listening rotation. But

Ziggy remains strong for me in large part because I never left it; it became one of my musical homes during my teens that I still regularly visit.

Back in the early '90s, Jungle brought reggae and dancehall elements into the rave scene. Within a few years, drum and bass evolved and moved on to wider sounds. Barry Ashworth and Dub Pistols call back to that era, mining the jungle sounds and updating it. On their latest, Worshipping the Dollar, the band offers a cool mix of ska, dub style reggae, and hip hop that's been mashed up with drum and bass to satisfy a clubby, pop-centric ear.

Back in the early '90s, Jungle brought reggae and dancehall elements into the rave scene. Within a few years, drum and bass evolved and moved on to wider sounds. Barry Ashworth and Dub Pistols call back to that era, mining the jungle sounds and updating it. On their latest, Worshipping the Dollar, the band offers a cool mix of ska, dub style reggae, and hip hop that's been mashed up with drum and bass to satisfy a clubby, pop-centric ear.

While David Bowie had achieved some commercial success with Space Oddity, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars transformed Bowie into a larger than life character. It's important to understand that Ziggy was not just music; it was a full blown persona, a story, and a fashion palette. Along with Marc

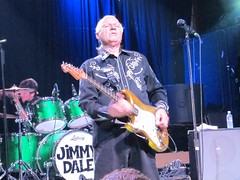

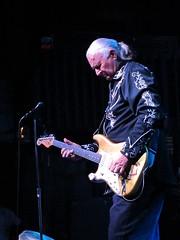

While David Bowie had achieved some commercial success with Space Oddity, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars transformed Bowie into a larger than life character. It's important to understand that Ziggy was not just music; it was a full blown persona, a story, and a fashion palette. Along with Marc  Don't worry about the pun in the title, this is anything but a comedy album. This is a country rocking, blues wailing, soul screaming message from the depths of the dirty South.

Don't worry about the pun in the title, this is anything but a comedy album. This is a country rocking, blues wailing, soul screaming message from the depths of the dirty South.

If albums are dinosaurs in these short attention span times, then the concept album is primordial. Retro psychedelic or overwrought progressive bands may exhume the format, but it's an old school play.

If albums are dinosaurs in these short attention span times, then the concept album is primordial. Retro psychedelic or overwrought progressive bands may exhume the format, but it's an old school play. I first heard about Detroit retro-rockers

I first heard about Detroit retro-rockers

Montreal rockers

Montreal rockers