Musical tiles coalesce into a more complicated mosaic

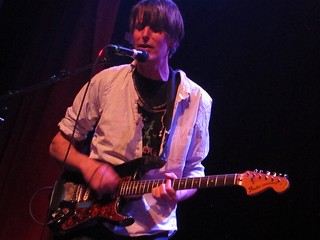

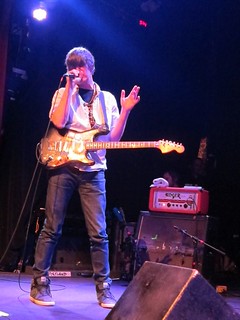

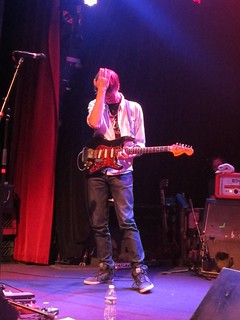

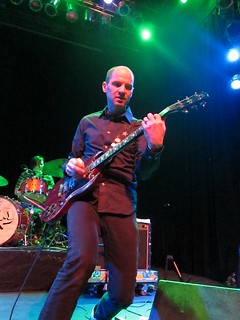

Matt Stevens’ latest solo sketchbook borrows cubist techniques to deconstruct his musical aesthetic and juxtapose all of the perspectives into a single work. Any given point has its locus of continuity and the songs flow into one another in a meaningful way, but on first impression, the project as a whole seems scattershot as it slides from driving post-rock through acoustic art rock to jazzy interludes. But it turns out that Lucid is well-titled, after all. Step back and take a look at the album in toto and you'll see that Stevens draws on the looped guitar experiments of his early work and the more intense exploration of his recent work with The Fierce and the Dead to assert himself. Like Walt Whitman, he is large, he contains multitudes. And although he lets all of these musical personas loose, he’s also invited a host of talented players to join Any given angle or track provides a different window on Stevens’ development as a player.

Matt Stevens’ latest solo sketchbook borrows cubist techniques to deconstruct his musical aesthetic and juxtapose all of the perspectives into a single work. Any given point has its locus of continuity and the songs flow into one another in a meaningful way, but on first impression, the project as a whole seems scattershot as it slides from driving post-rock through acoustic art rock to jazzy interludes. But it turns out that Lucid is well-titled, after all. Step back and take a look at the album in toto and you'll see that Stevens draws on the looped guitar experiments of his early work and the more intense exploration of his recent work with The Fierce and the Dead to assert himself. Like Walt Whitman, he is large, he contains multitudes. And although he lets all of these musical personas loose, he’s also invited a host of talented players to join Any given angle or track provides a different window on Stevens’ development as a player.

My first introduction to Stevens was his 2010 solo album Ghost (review), with its wonderfully evocative acoustic guitar loops and jazzy touches. Some of the new tunes call back to Ghost’s sound, like the Beatlesque jazz of “KEA” or the Latin-tinged post-rock of “The Other Side”, which is reminiscent of Ghost’s “Burnt Out Car”. At the same time, Stevens’ heavier tone with The Fierce and the Dead is also well represented, especially on standout tracks like “Unsettled”. Bandmate Stuart Marshall provides the phenomenal drum work that locks the tune down with taut rhythms and tight flourishes. Marshall’s cage barely holds the flailing tantrum of guitar in check. That discipline supports the raw chaotic expression, creating a dynamo of energy that sounds like some kind of head-banging King Crimson mutant. Speaking of Crimson, drummer Pat Mastelotto lends his solid, open-fill drumming to the angular guitar exercise of “The Ascent”. The progression is torn from the Robert Fripp handbook, but the metallic guitar borrows more from players like Steve Vai. Stevens channels a vein of pure emotion and vents out against the mathematical structure of the piece.

That passion and flair set up the sharp transition to my favorite track on Lucid, “Coulrophobia”. “The Ascent” drops away, leaving a vacuum. Tentative, moody notes drip softly into a starlit pool, like Porcupine Tree covering “Echoes” by Pink Floyd. A nervous shimmer of tension lurks at the edges, but never quite comes into focus. Like a dream, there is no control as the tune slowly unfolds at a calculated pace. The nervous energy can’t shake the calm lack of volition and it builds towards a thin trickle of terror. The piece summons more of a sense of sleep paralysis than scary clowns for me, but the savory element of fear certainly comes through. Unfortunately, the song is over all too quickly, moving on to the moody drive of the title track.

In fact, with the exception of the epic piece, “The Bridge”, which runs almost 12 minutes, most of these songs are shorter vignettes. This is what gives Lucid its sketchbook feel, but this, too, is part of Stevens' artistic sense. Where many of his post-rock peers drag out their songs into long-running feasts, he prefers to make instrumental tapas, which showcase a idea with clarity and then set up the next exciting flavor. Lucid collects all of these into strange collection of contrasts and surprises, but the net result is a great musical meal.

Matt Stevens’ latest solo sketchbook borrows cubist techniques to deconstruct his musical aesthetic and juxtapose all of the perspectives into a single work. Any given point has its locus of continuity and the songs flow into one another in a meaningful way, but on first impression, the project as a whole seems scattershot as it slides from driving post-rock through acoustic art rock to jazzy interludes. But it turns out that Lucid is well-titled, after all. Step back and take a look at the album in toto and you'll see that Stevens draws on the looped guitar experiments of his early work and the more intense exploration of his recent work with The Fierce and the Dead to assert himself. Like Walt Whitman, he is large, he contains multitudes. And although he lets all of these musical personas loose, he’s also invited a host of talented players to join Any given angle or track provides a different window on Stevens’ development as a player.

Matt Stevens’ latest solo sketchbook borrows cubist techniques to deconstruct his musical aesthetic and juxtapose all of the perspectives into a single work. Any given point has its locus of continuity and the songs flow into one another in a meaningful way, but on first impression, the project as a whole seems scattershot as it slides from driving post-rock through acoustic art rock to jazzy interludes. But it turns out that Lucid is well-titled, after all. Step back and take a look at the album in toto and you'll see that Stevens draws on the looped guitar experiments of his early work and the more intense exploration of his recent work with The Fierce and the Dead to assert himself. Like Walt Whitman, he is large, he contains multitudes. And although he lets all of these musical personas loose, he’s also invited a host of talented players to join Any given angle or track provides a different window on Stevens’ development as a player.My first introduction to Stevens was his 2010 solo album Ghost (review), with its wonderfully evocative acoustic guitar loops and jazzy touches. Some of the new tunes call back to Ghost’s sound, like the Beatlesque jazz of “KEA” or the Latin-tinged post-rock of “The Other Side”, which is reminiscent of Ghost’s “Burnt Out Car”. At the same time, Stevens’ heavier tone with The Fierce and the Dead is also well represented, especially on standout tracks like “Unsettled”. Bandmate Stuart Marshall provides the phenomenal drum work that locks the tune down with taut rhythms and tight flourishes. Marshall’s cage barely holds the flailing tantrum of guitar in check. That discipline supports the raw chaotic expression, creating a dynamo of energy that sounds like some kind of head-banging King Crimson mutant. Speaking of Crimson, drummer Pat Mastelotto lends his solid, open-fill drumming to the angular guitar exercise of “The Ascent”. The progression is torn from the Robert Fripp handbook, but the metallic guitar borrows more from players like Steve Vai. Stevens channels a vein of pure emotion and vents out against the mathematical structure of the piece.

That passion and flair set up the sharp transition to my favorite track on Lucid, “Coulrophobia”. “The Ascent” drops away, leaving a vacuum. Tentative, moody notes drip softly into a starlit pool, like Porcupine Tree covering “Echoes” by Pink Floyd. A nervous shimmer of tension lurks at the edges, but never quite comes into focus. Like a dream, there is no control as the tune slowly unfolds at a calculated pace. The nervous energy can’t shake the calm lack of volition and it builds towards a thin trickle of terror. The piece summons more of a sense of sleep paralysis than scary clowns for me, but the savory element of fear certainly comes through. Unfortunately, the song is over all too quickly, moving on to the moody drive of the title track.

In fact, with the exception of the epic piece, “The Bridge”, which runs almost 12 minutes, most of these songs are shorter vignettes. This is what gives Lucid its sketchbook feel, but this, too, is part of Stevens' artistic sense. Where many of his post-rock peers drag out their songs into long-running feasts, he prefers to make instrumental tapas, which showcase a idea with clarity and then set up the next exciting flavor. Lucid collects all of these into strange collection of contrasts and surprises, but the net result is a great musical meal.

It all begins with an organic splash of guitar, wrapped in a light haze of feedback. Anticipation continues to build as

It all begins with an organic splash of guitar, wrapped in a light haze of feedback. Anticipation continues to build as  It’s a bittersweet pleasure to listen to Uncle Tupelo’s debut album No Depression with 24 years of hindsight. You can hear the band discovering themselves and developing their sound. It’s a snapshot from before the rancor set in. Their label, Rockville Records, hadn’t screwed them yet and the power struggle between Jay Farrar and Jeff Tweedy still lay ahead. Even though the acrimony and split would lead to Farrar’s Son Volt and Tweedy’s Wilco, each of which have made some great music, it’s painful to listen to the band bare themselves in these raw songs and think of what would follow. Their simple sincerity and naïveté made this big impact that the band itself could not outlast and their debut remains fresh and relevant. No Depression captures the beginning of a groundswell that had its roots in the cow punk sounds of X, the Blasters and the Beat Farmers. Tempered by firmer leanings toward folk rock and country, this album has been largely credited with spawning a new genre that never came up with a good enough name; alt-country, Americana or the eponymous “No Depression” have all sat in as labels, but none quite satisfy. Less than a name, it all comes down to the music and attitude.

It’s a bittersweet pleasure to listen to Uncle Tupelo’s debut album No Depression with 24 years of hindsight. You can hear the band discovering themselves and developing their sound. It’s a snapshot from before the rancor set in. Their label, Rockville Records, hadn’t screwed them yet and the power struggle between Jay Farrar and Jeff Tweedy still lay ahead. Even though the acrimony and split would lead to Farrar’s Son Volt and Tweedy’s Wilco, each of which have made some great music, it’s painful to listen to the band bare themselves in these raw songs and think of what would follow. Their simple sincerity and naïveté made this big impact that the band itself could not outlast and their debut remains fresh and relevant. No Depression captures the beginning of a groundswell that had its roots in the cow punk sounds of X, the Blasters and the Beat Farmers. Tempered by firmer leanings toward folk rock and country, this album has been largely credited with spawning a new genre that never came up with a good enough name; alt-country, Americana or the eponymous “No Depression” have all sat in as labels, but none quite satisfy. Less than a name, it all comes down to the music and attitude.

Too many neo-psychedelic bands mistake freeform anarchy for true psychedelia, thinking that a confused and disoriented listener is functionally equivalent to one who’s been transported. Others assume that they can alchemically transform formulaic progressions into gold if they wrap them in enough distortion and echo. On Maui Tears,

Too many neo-psychedelic bands mistake freeform anarchy for true psychedelia, thinking that a confused and disoriented listener is functionally equivalent to one who’s been transported. Others assume that they can alchemically transform formulaic progressions into gold if they wrap them in enough distortion and echo. On Maui Tears,  Mothers can be nurturing and loving, but they can also be fierce.

Mothers can be nurturing and loving, but they can also be fierce.